The Amazon Basin: Earth's Greatest Watershed

The Amazon Basin represents Earth's largest river drainage system of waterways, floodplains, and ecosystems. This immense watershed collects rainfall and runoff across much of South America, channeling this vast flow through the world's mightiest river system to the ocean.

Waters of Life: The Amazon Basin's Hydrological Marvel

The Amazon Basin represents Earth's largest river drainage system, encompassing 6.3 million square kilometers (2.4 million square miles) of interconnected waterways, floodplains, and terrestrial ecosystems. This immense watershed—equivalent in size to the contiguous United States—collects rainfall and runoff across 40% of South America, channeling this vast flow through the world's mightiest river system to the Atlantic Ocean.

Shaped by millions of years of geological processes, particularly the rise of the Andes Mountains, the basin functions as a continental-scale depression that captures and redistributes water, nutrients, and sediments across an entire subcontinent. The basin's gentle topography and complex hydrological cycles create the conditions necessary for the world's largest tropical rainforest while supporting over 30 million people and countless species adapted to its rhythms of flood and drought.

As the geographical heart of Amazônia, this vast watershed defines the boundaries of South America's most significant biogeographic region, encompassing not only the physical drainage basin but also the cultural and ecological systems that have evolved within its embrace.

Geological Foundation and Formation

Tectonic Origins

The Amazon Basin's formation began approximately 140 million years ago during the Cretaceous period, when the Andes Mountains started their dramatic uplift. As the Nazca Plate subducted beneath the South American Plate, the resulting mountain chain created a massive topographical barrier that fundamentally altered the continent's drainage patterns.

Before the Andean uplift, rivers flowed westward into the Pacific Ocean. The rising mountains gradually reversed this flow, creating a vast inland depression that collected sediments eroded from the growing peaks. Over millions of years, this tectonic activity shaped the basin's current configuration—a gently sloping plain tilted eastward toward the Atlantic.

Sedimentary Architecture

The basin contains sedimentary deposits up to 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) thick, representing millions of years of Andean erosion. These sediments form distinct geological layers:

Basement Complex: Ancient Precambrian rocks form the basin's foundation, exposed in the Guiana Shield to the north and Brazilian Shield to the south.

Paleozoic Sediments: Marine and continental deposits from 540-250 million years ago, containing important fossil records and some petroleum reserves.

Mesozoic-Cenozoic Fill: The most recent 140 million years of deposition, primarily continental sediments from Andean erosion, forming the soils that support today's ecosystems.

Modern Landscape Evolution

The basin continues evolving through ongoing geological processes:

Isostatic Adjustment: The weight of accumulated sediments causes gradual subsidence, maintaining the basin's depression.

River Meandering: Major rivers continuously reshape the landscape through lateral erosion and sediment deposition.

Neotectonics: Subtle ongoing tectonic movements influence river courses and drainage patterns.

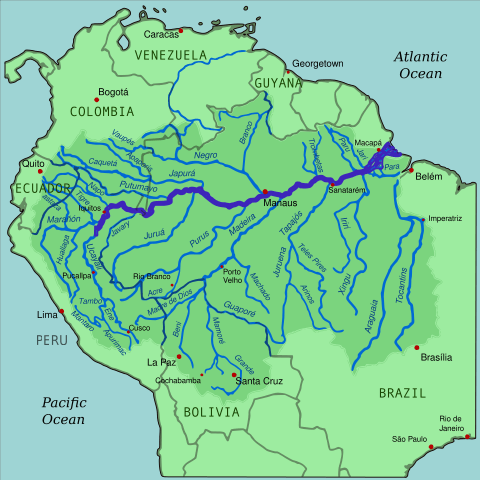

Map depicting the Amazon River drainage basin with the Amazon River highlighted.

Hydrological Architecture

Drainage Network Hierarchy

The Amazon's drainage network follows a hierarchical structure with the main stem supported by increasingly smaller tributaries:

First-Order Streams: Thousands of headwater channels draining individual hillslopes and forest patches.

Major Tributaries: Rivers like the Madeira (3,250 km/2,020 miles), Negro (2,250 km/1,400 miles), and Xingu (1,980 km/1,230 miles) that are among the world's largest rivers in their own right.

The Amazon River: The main stem integrates all tributary flows into a single channel, carrying 209,000 cubic meters (7.4 million cubic feet) of water per second to the Atlantic.

Water Types and Chemistry

Amazonian waters exhibit remarkable chemical diversity, classified into three distinct types based on their source regions and dissolved constituents:

Whitewater Rivers: Originating in the geologically young Andes, these rivers carry high loads of suspended sediment (200-400 mg/L) and nutrients. The Amazon main stem, Madeira, and Ucayali exemplify this type, supporting productive várzea floodplain ecosystems.

Blackwater Rivers: Draining ancient, heavily weathered shields, these rivers appear dark brown due to dissolved organic compounds called humic substances. The Rio Negro, the world's largest blackwater river, has pH levels as low as 4.5 and supports specialized fish communities adapted to acidic conditions.

Clearwater Rivers: Flowing from the Brazilian and Guiana shields, these rivers have intermediate characteristics with low sediment loads but higher pH than blackwater systems. The Tapajós and Xingu rivers represent this type.

Seasonal Hydrological Cycles

The basin experiences complex seasonal variations driven by precipitation patterns across its vast area:

Flood Pulse Dynamics: Water levels fluctuate 10-15 meters (33-49 feet) annually in many areas, with timing varying across the basin. Northern tributaries peak during June-August, while southern tributaries peak during February-April.

Hydrological Connectivity: During peak floods, normally separate river systems may connect through temporary channels, allowing fish migration and genetic exchange between populations.

Groundwater Interactions: The basin contains massive groundwater reserves, with some estimates suggesting underground water storage equivalent to the Amazon River's 20-year flow.

Topographical Diversity

Elevation Gradients

Despite its reputation as a flat lowland, the Amazon Basin contains remarkable topographical diversity:

Andean Foothills: Western margins reach elevations of 500-1,000 meters (1,640-3,280 feet), creating steep gradients and rapid streams.

Central Lowlands: Most of the basin lies below 200 meters (656 feet) in elevation, with gradients as gentle as 2 centimeters per kilometer (1 inch per mile).

Shield Uplands: Ancient rock formations create isolated highlands like the Guiana Shield's tepuis, rising to over 3,000 meters (9,840 feet) and hosting unique endemic ecosystems.

Geomorphological Features

The basin's landscape includes diverse landforms created by water action over millions of years:

Floodplains: Covering 150,000 square kilometers (58,000 square miles), these annually flooded areas represent some of Earth's most dynamic landscapes.

Terraces: Step-like formations along river valleys record past flood levels and climate conditions.

Oxbow Lakes: Abandoned river channels create thousands of crescent-shaped lakes that serve as fish refugia and biodiversity hotspots.

Levees: Natural embankments along rivers create elevated areas that remain above flood levels and support distinct plant communities.

Hydroclimatic Interactions

The Basin as a Weather Generator

The Amazon Basin functions as a massive atmospheric water recycling system, generating approximately 50% of its own precipitation through forest evapotranspiration.

Evapotranspiration Rates: Forest areas release 4-8 millimeters (0.16-0.31 inches) of water daily into the atmosphere—equivalent to 1,200-2,400 liters per square meter annually.

Atmospheric Rivers: Moisture evaporated from the basin travels thousands of kilometers, influencing precipitation patterns across South America and even reaching North America and Europe.

Precipitation Recycling: Water molecules may evaporate and precipitate multiple times as they cross the basin, with some estimates suggesting individual molecules travel over 3,000 kilometers (1,860 miles) before reaching the Atlantic.

Climate Regulation Functions

The basin's vast water surfaces and vegetation moderate the regional and global climate:

Temperature Buffering: Large water bodies moderate temperature extremes, maintaining relatively stable conditions across the basin.

Carbon-Climate Feedbacks: Vegetation growth responds to precipitation patterns, influencing carbon storage and atmospheric CO₂ concentrations.

Albedo Effects: Different land cover types reflect varying amounts of solar radiation, influencing local and regional temperature patterns.

Biodiversity and Aquatic Ecosystems

Aquatic Species Richness

The Amazon Basin supports the world's most diverse freshwater fish fauna, with over 3,000 described species and possibly 5,000 total species.

Endemic Families: Entire fish families like the Arapaimidae (arapimas) and many characid groups exist only in Amazonian waters.

Ecological Specializations: Species range from tiny tetras to 200-kilogram (440-pound) pirarucu (Arapaima gigas), the world's largest scaled freshwater fish.

Reproductive Strategies: Many species time reproduction with flood cycles, using flooded forests as nurseries for juvenile fish.

Floodplain Ecosystems

The basin's extensive floodplains support unique ecological communities adapted to annual flood-drought cycles:

Floating Meadows: Grass species like Echinochloa polystachya form vast floating mats during high water periods.

Flood-Adapted Trees: Species like Cecropia and Salix can survive months of complete submersion through specialized root systems and metabolic adaptations.

Temporary Wetlands: Seasonal lakes and marshes provide critical habitat for fish spawning and bird feeding.

Terrestrial-Aquatic Connections

The basin's terrestrial and aquatic systems interact in complex ways:

Fruit-Fish Interactions: Over 200 fish species feed on fruits and seeds from flooded forests, serving as seed dispersers for terrestrial plants.

Nutrient Subsidies: Seasonal floods transport nutrients between terrestrial and aquatic systems, supporting productivity in both environments.

Habitat Mosaics: The dynamic interface between land and water creates diverse microhabitats supporting specialized species communities.

Human Dimensions and Cultural Geography

Indigenous River Cultures

For over 11,000 years, human societies have adapted to the basin's hydrological rhythms:

Flood-Pulse Agriculture: Indigenous groups practice várzea agriculture, planting crops on fertile floodplain soils exposed during low water periods.

River Navigation: Traditional knowledge includes a sophisticated understanding of seasonal navigation routes, reading water levels, and predicting flood timing.

Aquatic Resource Management: Indigenous communities have developed sustainable fishing practices, including seasonal restrictions, species-specific techniques, and rotational use of fishing areas.

Contemporary Settlement Patterns

Modern human settlement reflects the basin's hydrological geography:

Riverine Cities: Major cities like Manaus, Iquitos, and Leticia developed as river ports, serving as transportation and commerce hubs.

Floodplain Communities: Ribeirinho (riverbank) communities practice mixed economies combining fishing, small-scale agriculture, and forest product extraction.

Urban Challenges: Cities face unique challenges from seasonal flooding, water treatment, and waste management in aquatic environments.

Transportation Networks

The basin's river system serves as South America's longest highway network:

Commercial Navigation: Ocean-going vessels can reach Manaus, 1,500 kilometers (930 miles) inland, making it one of the world's most inland major ports.

Regional Connectivity: Smaller boats connect thousands of riverside communities, carrying people, goods, and services throughout the basin.

Economic Integration: Rivers facilitate trade between Andean highland regions and lowland areas, integrating diverse ecological zones economically.

Environmental Pressures and Changes

Deforestation Impacts

Forest clearing throughout the basin creates cascading hydrological effects:

Reduced Evapotranspiration: Deforested areas release less water vapor, potentially reducing regional precipitation by 10-20%.

Increased Runoff: Without forest canopies and root systems, more precipitation becomes direct runoff, increasing flood peaks and erosion.

Sedimentation: Erosion from cleared areas increases river sedimentation, affecting aquatic habitats and navigation.

Climate Change Vulnerabilities

The basin faces multiple climate-related threats:

Precipitation Pattern Changes: Models predict increased dry season intensity, potentially stressing both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.

Temperature Increases: Warming waters could exceed thermal tolerance limits for many fish species.

Extreme Events: More frequent droughts and intense floods could disrupt the functioning of ecosystems and human communities.

Infrastructure Impacts

Large-scale development projects alter basin hydrology:

Hydroelectric Dams: Over 150 dams are planned or under construction on Amazon tributaries, which could fragment river systems and alter flood cycles.

Navigation Projects: Channel deepening and straightening projects change natural flow patterns.

Mining Activities: Large-scale mining operations affect water quality and sediment loads in tributary systems.

Conservation and Management Challenges

Transboundary Coordination

Effective basin management requires international cooperation across nine countries with varying priorities and capacities:

Water Resource Treaties: The Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization provides a framework for coordinated management, though implementation remains challenging.

Shared Species Management: Fish populations migrate across multiple countries, requiring coordinated conservation efforts.

Pollution Control: Contamination in one country's territory affects downstream nations, necessitating basin-wide environmental standards.

Integrated Watershed Management

The basin's size and complexity require innovative management approaches:

Ecosystem Service Valuation: Quantifying the basin's hydrological services helps justify conservation investments.

Adaptive Management: Management strategies must accommodate natural variability and uncertainties related to climate change.

Community-Based Conservation: Local communities often possess detailed knowledge essential for effective conservation.

Monitoring and Research

Understanding basin-wide processes requires sophisticated monitoring systems:

Hydrological Networks: Gauging stations throughout the basin track water levels, flow rates, and water quality parameters.

Satellite Monitoring: Remote sensing provides basin-wide data on land cover changes, flood extent, and vegetation health.

Biodiversity Assessments: Ongoing species inventories reveal the full extent of the basin's biological diversity.

Future Trajectories

Sustainable Development Pathways

The basin's future depends on balancing human needs with ecological integrity:

Green Infrastructure: Natural floodplains and wetlands provide flood control and water purification services more cost-effectively than engineered alternatives.

Sustainable Fisheries: Well-managed fish populations can provide protein for millions of people while maintaining ecosystem health.

Ecotourism Potential: The basin's natural wonders attract visitors worldwide, providing economic incentives for conservation.

Restoration Opportunities

Degraded areas throughout the basin offer restoration potential:

Reforestation Projects: Restoring forest cover in degraded areas can partially restore hydrological functions.

Floodplain Restoration: Reconnecting rivers with their floodplains enhances flood control and fish habitat.

Wetland Conservation: Protecting remaining wetlands maintains their critical water purification and carbon storage functions.

Conclusion: The Basin's Global Significance

The Amazon Basin represents far more than a regional watershed—it is a planetary life-support system whose health affects global climate stability, freshwater resources, and biodiversity conservation. This vast hydrological network regulates continental weather patterns, stores massive amounts of carbon, and supports an estimated 10% of known species.

As human pressures and climate change increasingly stress this system, understanding the basin's integrated functioning becomes critical for developing effective conservation and management strategies. The basin's complexity means that local actions can have basin-wide consequences, while global changes manifest in local impacts throughout the watershed.

Protecting the Amazon Basin requires recognizing it as an integrated geographic system where geological processes, hydrological cycles, ecological communities, and human societies interact across multiple spatial and temporal scales. This holistic perspective is essential for ensuring that Earth's greatest watershed continues to support the incredible diversity of life it has nurtured for millions of years while providing critical services to humanity and the global environment.